Unsplash.com/JC Gellidon

Just after Herman Melville published Moby Dick, and decades before that novel would be recognized as a classic, Melville penned a short story called "Bartleby the Scrivener." A scrivener, or a scribe, is essentially a public scribbler, similar to what secretaries did before the ease of computers gave lazy bosses no excuse not to do the work themselves. Reporters are scriveners. A little more than that, we’d like to think. They report what they see in documents. They try to translate it from the bureaucratic, but sometimes they're, well, lazy.

We’ve posted segments about “disqualifiers,” in which writers made fatal mistakes about history, anatomy and geography. Those subject areas also are rife with examples of writing that isn’t so much wrong as lazy. We often have said that good writing is about clarity. In that vein, we’ve said that sometimes it’s not a matter of using the right word but, rather, using a better word. Sometimes you have to try to know the mind of the reader. But we argue that it’s better to add a few words for those who aren’t sure.

A lazy reporter might write this: ‘Investigators have cited ‘spatial disorientation’ in Thursday's fatal crash off San Diego.”

An enterprising reporter might write this: “Socked in by fog in Southern California's notorious ‘June Gloom,’ the pilot in Thursday's fatal crash didn't know which way was up in the moments before he slammed into San Diego Bay, investigators have concluded.”

The second lead not only imparted more information, it provided a punch that made people want to read the story.

An article on a 2019 Bahamas helicopter crash listed "spatial disorientation," but never said what it is! The reader can kind of guess, but then she'd be doing the reporter's work. How hard would it have been to add the following paragraph, which Eliot did include in one of his plane crash report stories:

“...’spatial disorientation,’ a sometimes-fatal bane of pilots, in which they lose all visual contact with the ground or ocean and even the horizon, as well as their grip on their speed, location, and direction, and even if they’re facing up.”

That not only helps the reader, it again provides even more punch.

In journalism school, we were taught, “‘assume’ makes an ‘ass’ out of ‘u’ and ‘me.’” It still is a good rule. In July 2021, a story about a CNN documentary on the “sitcom” never defined “sitcom.” The term’s been around so long, most readers probably don’t know it’s a contraction of “situation comedy,” which, when you say it, makes the concept of a “sitcom” crystal clear. Don’t assume!

Here’s an example that comes right down to your front yard. At times, Eliot arranged for his lawn to be sprayed for bugs. He’d come home at the end of the day to find the sign at top. Here’s a typical phone conversation:

“I’m home. You sign says to stay off until the lawn is dry. Is it?”

”Yes. It was dry about two hours after we applied the treatment.”

”When did you apply it?”

”About 2 p.m.”

”How was I supposed to know that?“

Silence.

”So it’s dangerous for my children and my pets to go on the lawn before it’s dry. But you’ve not given me a clue as to when that is.”

We’ve called this the “contempt of familiarity.” How hard would it be to grab a Sharpie, as shown in the second sign?

The third sign had the right design, but, well, the technician forgot his Sharpie.

The fourth sign did include a Sharpie, but the time the pesticide was applied is worthless if the sign doesn’t say how long it takes for the lawn to dry.

A minor nit? Not if your two-year-old shoots out the front door and face-plants in the lawn.

Here are more examples where the writer failed to take a few extra minutes to make the story more clear. Or just assumed (!!!!!!!) the reader knew what he/she meant. And, maybe, aggravated the transgression by including unnecessary stuff!

1. “The new restaurant is at 9560 Glades Road, Suite 115.”

“The new restaurant is on Glades Road, across from the Palm Beach County Library, between Lyons Road and State Road 7.” Don’t presume your readers, who could live far from the place about which you’re writing, have a clue what that address means. Sure, nowadays, they just can look it up on their phone. But remember: anytime a reader has to stop reading your story to look up something you wrote, you’ve failed. And why bother with the suite number?

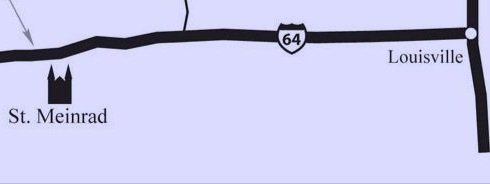

2. “Schnellenberger was born on March 16, 1934, in Saint Meinrad, Indiana. His parents were German-American. The family eventually moved to Louisville…”

Eliot’s wife is from Indiana and neither she nor her mother ever heard of Saint Meinrad. How about: “Schnellenberger was born to German-American parents on March 16, 1934, in Saint Meinrad, Indiana, about an hour west of Louisville, to where his family eventually moved.”

3. “Oak Park is about 9 miles from Chicago.”

The center of Oak Park might be 9 miles from the center of Chicago, but if you walk east from the Oak Park village hall (Eliot’s done it), you cross into the city of Chicago not in 9 miles, but in about 8 blocks. Say, “Oak Park is about 9 miles west of downtown Chicago.” (And yes, we did drop in “west of” for clarity.)

4. “Cincinnati police say the shooting suspect had bought his gun in Lawrenceville, Ga.”.

See #1. Do people in Cincinnati know where Lawrenceville, Ga. is? Most probably don’t. How hard is it to say, “…bought his gun in the Atlanta suburb of Lawrenceville, Ga.”

5. “Police said the man fractured his ulna.”

“Police said the man fractured his forearm.”

YouTube

6 “In 1990, Bush loved to go bonefishing in the Keys with the likes of Brian Mulroney.”

Americans are shamefully ignorant of that big country just north of them. We have to help them. Did you know who Brian Mulroney was? Maybe. In this case, adding just four words makes sure: “In 1990, Bush loved to go bonefishing in the Florida Keys with the likes of then-Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.” (Yes, sharp readers; we added a fifth word, “Florida.” Because most people in North America know the Keys are in Florida, but not all.)

FBI

7. “When he arrived in Washington to take his seat in Congress, Anderson moved into a townhouse once owned by Alger Hiss.”

See “Mulroney.” Many people today weren’t alive in 1948. Say: “When he arrived in Washington to take his seat in Congress, Anderson moved into a townhouse once owned by Alger Hiss, the federal staffer accused in 1948 of having spied for the Soviet Union.”

Watch this on video! https://youtu.be/3y6r-xFW9Ig

Next time: What’s in the stew?

Readers: "Something Went Horribly Wrong," features samples of bad writing we see nearly every day. You can participate! Be our duly deputized “grammar police:” Your motto: “To protect and correct.” Send in your photos of store signs, street signs, newspaper headlines, tweets, and so on. It doesn’t have to be a grammatical error. It can be just what we call “cowardly writing.” Include your name and home town so we properly can credit you. You're free to add a comment, although we reserve the right to edit or omit. Now get out there! Send to Eliot@eliotkleinberg.com

Haven’t signed up for our newsletter yet? Do it now! And tell your friends!